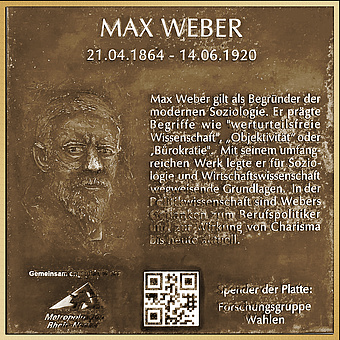

Max Weber (21.4.1864 - 14.06.1920)

Max Weber is considered the founder of modern sociology. He coined terms such as "value-judgment-free science", "objectivity" and "bureaucracy". With his extensive work, he laid groundbreaking foundations for sociology and economics. In politics, Weber's thoughts on the professional politician and the effect of charisma are still relevant today. Even those who do not know Max Weber have heard his statement "Politics is the drilling of thick boards.

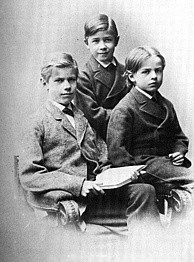

Maximilian Carl Ernst Weber was born in Erfurt on April 21, 1864, the first of eight children of Max Weber Sr., a lawyer and later a member of the Reichstag, and his wife Helene née Fallenstein.

Five years later, the family moved to Berlin. There Max attended the royal Kaiserin-Augusta-Gymnasium.

The somewhat sickly Max, sheltered by his mother, is quite a self-confident and inquisitive child. At the age of thirteen, he is already reading the works of Kant, Schopenhauer and Spinoza. It becomes apparent early on that he thinks independently and does not like to be pigeonholed.

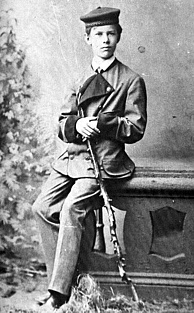

After graduating from high school in 1882, he enrolled in Heidelberg to study national economics, law, history and philosophy.

In October 1983, he interrupted his studies to do a year's voluntary military service in Strasbourg.

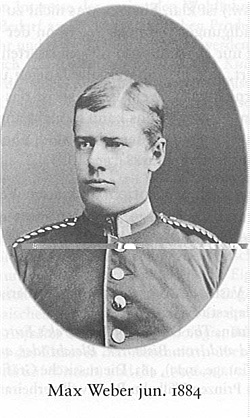

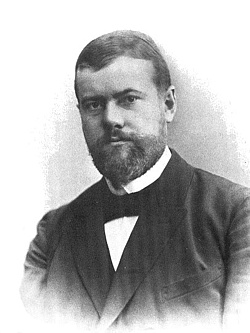

In 1884 he continued his studies in Göttingen and Berlin and received his doctorate in 1889, even before his second state law examination, with the distinction "magna cum laude".

Three years later, he habilitated with the topic "Roman Agricultural History in its Significance for Constitutional and Private Law.

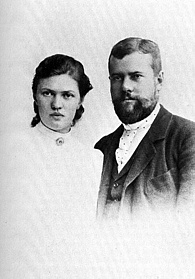

In 1893, at the age of only 29, became an associate professor of commercial law in Berlin. In the same year, he married his distant cousin Marianne Schnittger.

The later women's rights activist, sociologist and lawyer is elected to the Baden state parliament in 1919 as a member of the German Democratic Party and is the first woman to give a speech there.

In 1894, Max Weber was appointed professor of national economics at Freiburg, but just two years later he moved to the Ruprecht Karls University in Heidelberg.

In the same year, his first sociological essay "The Social Reasons for the Decline of Ancient Culture" is published. The eloquent Weber ensures full lecture halls and fascinates his students with unconventional approaches.

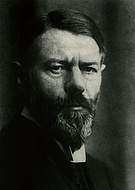

But already in 1898 he has to limit his teaching activities because of increasing depression and in 1903 he even has to give up his professorship. However, he continued to work as a private scholar and wrote his most important works in Heidelberg.

One of his most important works is "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism," published in 1904/05. In it, he describes Protestant ethics as an important force that led to rationalization in the economy. According to Weber, Puritan Calvinism in particular, with its asceticism, drove people to work, discipline and capital formation, thus promoting capitalism. The latter, however, eventually moved away from its ethical roots and favored a lifestyle in which people lived for rather than from their work.

Together with his colleagues Tönnies and Simmel, Weber founded the German Sociological Association in 1909.

In 1910, the couple moved into the stately "Haus Fallenstein," built by Weber's grandfather and located opposite Heidelberg Castle. Regular Sunday discussion circles are held there, at which politicians, scientists and intellectuals such as Friedrich Naumann, Gustav Radbruch, Karl Jaspers, Georg Simmel, Ernst Troeltsch and Ernst Bloch are guests and establish the "myth of Heidelberg". Haus Fallenstein still exists and is used today as the Heidelberg University College for German Language and Culture.

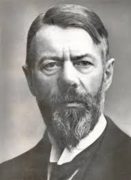

At the beginning of World War I, Weber volunteers as a reserve lieutenant and administers the hospital commission in Heidelberg for a year. In September 1917, he accepts a professorship at the University of Vienna, but returns to Heidelberg and his wife a few months later. After the end of the war, Weber participates as a delegate in the peace conference on the Treaty of Versailles.

As a private scholar, he gives numerous lectures in Heidelberg on topics such as "Germany's Reconstruction," "The Coming Imperial Constitution," and "The Free People's State." In the summer semester of 1919, he accepted a position as professor of social science, economic history and national economics at the University of Munich and witnessed the violent suppression of the Munich soviet republic.

In his lecture "Politics as a Vocation," delivered in Munich in 1919, Max Weber explores the question of what kind of person one must be "in order to be allowed to put one's hand into the spokes of history." For Weber, politics is not a profession, but a vocation. That's why he dislikes professional politicians who are looking to be re-elected. For him, ethics of responsibility counts more than ethics of attitude. Most famous is Weber's statement "One can say that three qualities are primarily decisive for the politician: passion, sense of responsibility, sense of proportion. Politics means a strong, slow drilling of hard boards with passion and sense of proportion at the same time." Who can argue with that? Not without reason is this sentence still often quoted today. Weber's thoughts on the professional politician and the effect of charisma are also current in political science.

In 1919, his lecture on "Science as a Profession," which had already been given in 1917, was published, in which Weber considers the career of science with its advantages and disadvantages as well as its chances for advancement and sheds light on the question of the value of science. "All the natural sciences give us an answer to the question: what should we do if we want to technically master life? But whether we should and want to control it technically, and whether that actually makes sense in the end: - they leave that entirely open or presuppose it for their purposes." For Weber, science is above all a tool for independent thinking.

Weakened by restless work, Max Weber fell ill with the Spanish flu that was raging in Munich and died on June 14, 1920, at the age of only 56. His wife Marianne buries Weber's urn in Heidelberg's Bergfriedhof and delivers the eulogy before a large mourning congregation.

In the years that followed, she also took care of the publication of his countless lectures and essays.

In 1920/21 Weber's main work "Economy and Society" is published, in which he presents his conceptual horizon in a comprehensive and interdisciplinary way.

Max Weber is considered the founder of sociology as a modern science and is still one of the most frequently cited sociologists. For Weber, sociology is a science free of value judgements. He describes it as a "science which seeks to understand social action interpretatively and thereby explain it causally in its course and effects."