Mannheim hours 1780

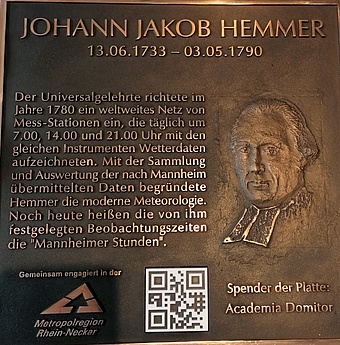

Johann Jacob Hemmer (1733 - 1790)

Today, we take it for granted to watch the weather report on television or to call up the weather forecast for the next few days on the Internet. In ancient times, people still believed that the weather was determined by the gods and tried to influence them by making offerings. The first systematic description of the phenomena of the air envelope was described by Aristotle in his book "Metereologica", which was still considered the standard textbook until the end of the 17th century. In the Middle Ages, weather observations were noted in house calendars and weather rules or farmers' calendars were developed from them, such as the "100-year calendar". But this had nothing to do with a weather forecast.

We have Johann Jakob Hemmer to thank for the first weather forecasts. He was born on June 13, 1733, the ninth of ten children of the small farmers Wilhelm and Anna Margaretha Hemmer in the small village of Horbach, near Kaiserslautern. Johann Jacob is an inquisitive child. His extraordinary talent becomes apparent at an early age. An organ playing impresses him so much that he wants to learn the instrument in 'Lautern', which is allowed to him after long pleading. When he met students of the Latin school, he wished to be allowed to learn there as well. Through the mediation of the parish priest Johann Stertzner, he is allowed to attend the Latin school.

But after just one year, his parents can no longer afford the school fees and Johann Jakob has to return to Horbach. However, he cannot accept a future as a farmer. He is too fascinated by the study of science. And so he decides to secretly leave his home and family. Penniless, he sets off for Cologne, where he makes his way as a wandering singer and lute player. In Cologne, too, he earns his living by playing the lute until he is finally accepted at the Jesuit Gymnasium. Soon he is awarded prizes there as the best in his class.

He becomes a tutor for the patrician family of Guaita and is able to finance his studies of philosophy and mathematics with his earnings. This was followed by theological studies at the Jesuit College. At his father's request, however, Johann Jakob renounces his religious vows and returns to the Palatinate. The priest Stertzner, who in the meantime had been transferred to Dirmstein, found Hemmer a position as a tutor with Baron Franz Georg von Sturmfeder, the chamberlain of Elector Carl Theodor.

On January 31, 1760, Hemmer was appointed court chaplain to the Elector. The ruler, who was as educated as he was generous, not only promoted the arts, such as the music of the Mannheim School, but also the natural sciences. Under Carl Theodor (7), Mannheim developed into a European center for science and music. The court library, which was open to general use, also ranked highly.

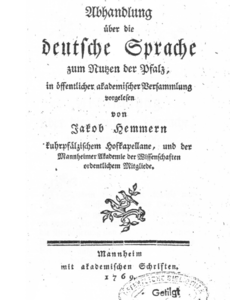

In April 1767, Hemmer became an associate member of the Palatine Academy of Sciences, which had been founded five years earlier, and a full member one year later. In addition to his scientific research, Hemmer also devoted himself to reforming the German language. The burghers and peasants, hardly any of whom can read, speak dialect, the educated French, and the scholars Latin. This does not seem to Hemmer to be suitable for the dissemination of science. He advocates writing words exactly as they are spoken and opposes the excessive use of foreign words. Nowadays, one often wishes for someone like Hemmer as well. Later, he even calls for the introduction of of lower case except for proper names and at the beginning of sentences.

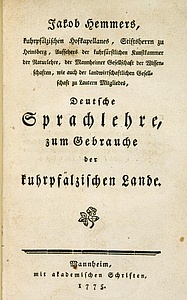

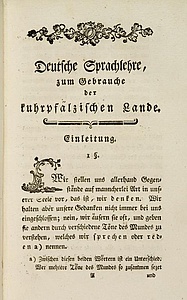

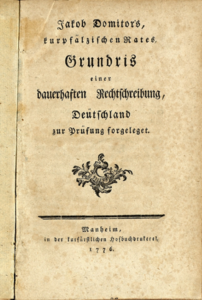

In 1769 Hemmer publishes his first work under the title "Abhandlung über die deutsche Sprache zum Nutzen der Pfalz". In 1771 followed his "Vertheidigungsschrift" and in 1775 his "Deutsche Sprachlehre zum Gebrauche der kurpfälzischen Lande". Under the Latin pseudonym Jakob Domitor (Bezwinger), his "Grundriss einer dauerhaften Rechtschreibung" (Outline of a Durable Orthography) appeared in 1776.

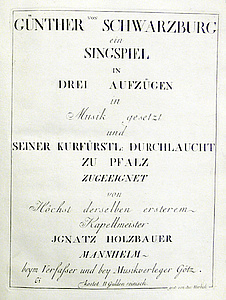

Hemmer's progressive language reform, however, could not prevail. But in 1775, the singspiel "Alceste" is performed in German at the electoral opera house, where until then only Italian had been sung. In 1777, Hemmer also witnessed the performance of the first German opera "Günter von Schwarzburg" by Ignaz Holzbauer, an important representative of the "Mannheim School". He will certainly also have seen the German play "Die Räuber" by the young poet Schiller, which premiered in January 1782, at the National Theater.

On behalf of the scientifically educated Elector Carl Theodor, who also liked to conduct physical experiments himself, Hemmer set up a physics cabinet in the palace pavilion between the opera house and the Jesuit College - where the district court is located today. It is equipped with scales, optical instruments, air pumps and measuring instruments such as thermometers and barometers. Apparatuses for the fashionable experiments with electricity are also not missing. The ladies and gentlemen of the society can experience such experiments at Hemmer's popular scientific lectures on "Erfahrungsnaturlehre. In this way, he contributes to the dissemination of scientific knowledge. In particular, his experiments on the phenomena of electricity attract great interest.

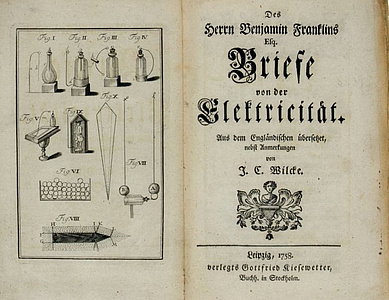

When the hall of Heidelberg Castle and the stables of Schwetzingen Castle were destroyed by lightning in 1764 and 1769 respectively, Hemmer became intensively involved with atmospheric electricity and the writings of Benjamin Franklin, one of the founders of the United States. Franklin had already proven in 1752 that lightning is the visible discharge of electrical energy and constructed the first lightning rod.

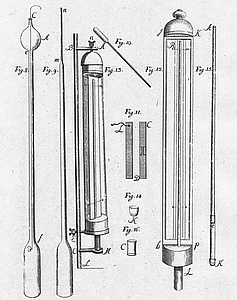

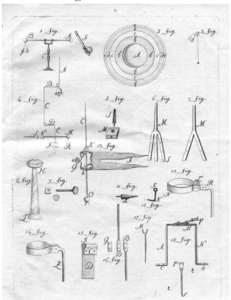

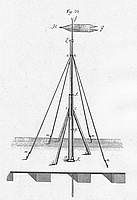

Hemmer further developed this simple rod into a "five-pointed" lightning rod with a vertical arresting rod and a horizontal beam cross pointing in all directions. A strong metal wire connects the "weather rod" to a lead plate sunk into the ground as grounding.

Hemmer convinces the Elector that his "weather conductor" can safely protect buildings. On February 27, 1776, Carl Theodor became the first German prince to order that all public buildings be protected from lightning strikes by Hemmer's "Fünfspitz".

It is certainly no coincidence that Hemmer installs his first "weather conductor" on the roof of Trippstadt Castle near Kaiserslautern in April 1776. The builder of the castle is Baron Franz Karl Josef von Hacke, the brother-in-law of Hemmer's former employer and patron Franz Georg Ernst von Sturmfeder.

As early as July 1776, lightning conductors were installed at the palace in Schwetzingen, the summer residence of the elector. They are still in use there today. In November, the powder towers in Heidelberg followed, and later also Mannheim Castle, the armory, the Old City Hall and St. Sebastian's Church. The Rohrbacher Schlösschen, the later tuberculosis hospital where Albert Fraenkel later worked, also received a lightning conductor.

But it will take a lot of education before the lightning conductors will prevail against reservations and resistance. Some consider them useless. For the God-fearing, it is sacrilegious to divert lightning, since it is an instrument of divine wrath against which one must not intervene. Only the loud ringing of bells was widely believed to drive away the storm. However, the commonly used "weather ringing" is not only ineffective, but often even dangerous. It was not uncommon for the bell ringer to be struck by lightning while ringing the bell. In 1784, at Hemmer's instigation, weather ringing was finally banned.

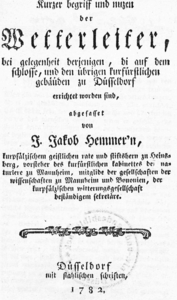

Hemmer published several enlightening pamphlets. These include the treatise "Kurzer begriff und nuzen der Wetterleiter" (Short concept and use of weather ladders) published in 1783, the "Anleitung, Wetterleiter an allen gattungen von gebäuden auf die sichererste Art anlegen" (Instructions for installing weather ladders on all types of buildings in the safest way) from 1786 and the "Verhaltensregeln, wenn man sich zur gewitterzeit in keinem bewaffneten gebäude befindet" (Rules of conduct if one is not in an armed building at the time of a thunderstorm) from 1789. He refutes the concerns and explains that one should not then "oppose the wild waters with dams, the rain with roofs, the cold with clothing and warm rooms. If it is a daring to keep the lightning away from the buildings, it must also be a daring to extinguish the fire. One would therefore have to watch the raging flames calmly, so as not to offend the divine will."

By the time of his death, more than 150 buildings in Munich and Düsseldorf had been fitted with lightning rods, and Hemmer himself supervised their installation, with a few exceptions.

Since time immemorial, people have wanted to know how the weather will develop. For example, whether they can let the grain ripen a little longer or whether a storm is about to threaten the harvest. But apart from wind vanes, rain gauges and farmers' rules, there are no aids. The thermometer was not invented until 1592 by Gallilei and the barometer for measuring atmospheric pressure in 1643 by Evangelisto Torricelli. In Italy and England, attempts were made as early as the second half of the 17th century to gain scientific knowledge by observing the weather. However, these attempts failed, as did a petition by the Karlsruhe physicist Johann Lorenz Böckmann to Margrave Karl Friedrich von Baden to set up a weather institute with observation stations at 16 locations in Baden.

At the Mannheim academy, Georg von Stengel is concerned with meteorology. His son Stephan, who follows Elector Carl Theodor to the new residence in Munich in 1778, explains the Mannheim weather observations to the Elector and compares them with those from Munich. Together with his father and Hemmer, he plans the foundation of a meteorological society and writes a petition to the Elector. The scientifically educated Carl Theodor expects advantages from this, especially for agriculture. He also wants to compensate Mannheim for his departure to Bavaria and gladly fulfills the request. He not only agrees to the foundation, but is even prepared to finance the costs from the cabinet coffers.

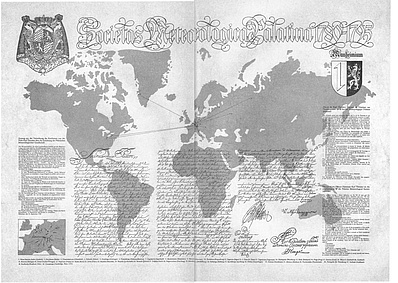

On September 15, 1780, Elector Carl Theodor signed the foundation charter of the "Societas Meteorologica Palatinae" in Munich. It states: "The sciences, which have a direct influence on the life of man and his daily occupations, deserve special consideration, attention and care. For these reasons, His Electoral Serene Highness has accorded weather science the highest protection and has arranged for daily observations to be made and collected at several important places in the Electoral Hereditary Lands, as well as in other parts of Europe and the rest of the world, using instruments as similar as possible." To achieve this goal, a metereological class is established at the Mannheim Academy of Sciences in addition to the historical and physical classes.

Johann Jacob Hemmer is appointed its secretary and he is assisted by the court astronomer and director of the new observatory, Christian Mayer, and the young astronomer Karl König. Especially the internationally respected Christian Mayer can help Hemmer to build up the first worldwide weather observation network through his contacts to other observatories, academies and monasteries. Because in order to understand the phenomena and developments of the weather and to make a forecast possible, many measuring stations distributed over a large area are necessary.

There is great international interest in participating. Only from England, Ireland and Vienna there is no response. But not only 14 stations all over Germany participate, but also in Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Holland, Belgium, France, Italy, Hungary and even Greenland, Russia and North America. The Mannheim station will be set up on the upper floor of the western castle tower.

Each of the 39 observing stations selected by Hemmer receives, at the Elector's expense, a package of specially made instruments such as barometers, thermometers, and a humidity meter developed by Hemmer. On request, a declination needle (deklinatorum magneticum) is also supplied, with which the deviations of the earth's magnetic field from the geographic north direction can be measured. In addition to instructions for building a wind direction meter, a table prepared by Hemmer is also provided in which the measurement results are to be entered.

Weather phenomena such as cloud cover, thunderstorms and the type of precipitation are to be marked with symbols specially designed for this purpose. Even observations about the flowering times of plants and the yields of crops, or the times of arrival and departure of migratory birds and pest infestations, should be entered. To ensure uniformity of operation, each package is accompanied by precise observation instructions. These instructions state, for example, how and where to hang the barometer and, above all, that the measuring instruments are to be read at the same times, i.e. at 7 a.m., 2 p.m. and 9 p.m. local time. These times are still called the "Mannheim hours" in meteorology today.

The data, which were often transmitted to Mannheim by ship or stagecoach only after a year, were evaluated by Hemmer and published in a total of 12 annual volumes of the Ephimerides starting in 1783. They represent the first data for a longer-term weather trend. By comparing the various measurement results, Hemmer is able to gain many meteorological insights and insights into the relationships between weather and climate.

The Ephimerides represent a unique source for scientific research. Alexander von Humboldt uses them for his comparative meteorology of 1817. Even today, the Ephimerides kept in the Reiß-Engelhorn Museums are still significant for historical research on the observation of climate changes.

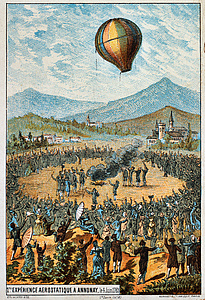

When the Montgolfier brothers launched the first hot-air balloons in Annonay in June and in Paris in the fall of 1783, Hemmer was so fascinated by them that he began to experiment with "air balls" himself. On April 14, 1784, the Mannheim newspaper reported on one of his experiments: "Today at noon, Professor Hemmer ...carried out experiments with the air ball in the castle courtyard. The smaller one of 18 inches in diameter .... rose slowly at first, then very quickly and rose to such a height that even the sharpest eye finally lost it. The larger one was made of paper and had 20 shoes in diameter. When one wanted to fill him after hung up furnace, a violent wind arose, which drove him violently on the side...the continuing force of the wind could not resist him at last, and this tore him into 2 pieces." Among the spectators was Friedrich Schiller, who was writing "Don Carlos" in Mannheim and reported on the attempt in a letter.

On April 28, 1790, when Hemmer was about to mount one of his weather bars at the Mannheim department store, he suddenly felt so bad that he went home and went to bed. The doctor, personal physician to Electress Elisabeth Augusta, notes that Hemmer had been tormented for two years by palpitations and a pulse that often skipped a beat, to the point of fainting. But the doctor was unable to help. Hemmer dies on May 3, 1790, at the age of only 59.

His death heralds the end of the "Societas Metereologica Palatinae". Less and less data are transmitted to Mannheim, the financial support by the Elector dries up. On November 21, 1795, the west wing of the palace is set on fire by Austrian cannons, destroying not only the opera house but also the physical and meteorological cabinets. The publication of the 12th volume of the Ephimerides in 1795 marks the end of the "Societas Metereologica Palatinae". Today, the only reminder of the former measuring stations is the observatory of the German Weather Service on the Hoher Peißenberg in Bavaria at 977 meters above sea level, the oldest mountain observatory in the world.

Johann Jacob Hemmer founded modern meteorology with the systematic measurements of his weather observation network and the standards he developed.