Leaf position theory 1834 Ice age theory 1835 Folded mountains 1840

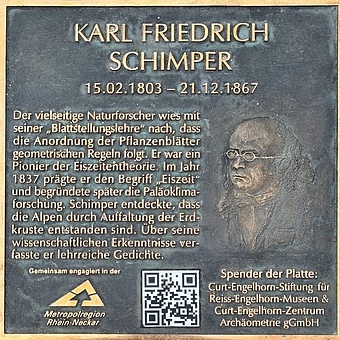

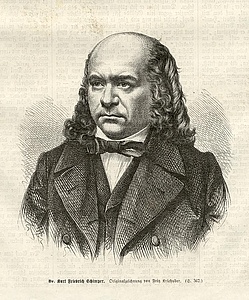

Karl Friedrich Schimper (1803-1867)

Karl Friedrich Schimper comes from a family that produced several important botanists. He was born in Mannheim on February 15, 1803, the son of the surveyor Friedrich Ludwig Heinrich Schimper and his wife, the Nuremberg patrician's daughter Margaretha, Freiin von Furtenbach, and was very proud of the fact that none other than Galileo Galilei saw the light of day on the same day. Schimper's brother Wilhelm was born one and a half years later.

The parents' marriage is not a happy one. The father loses his job and the family lives in extremely modest circumstances. Eventually, the marriage is divorced and the father moves to Petersburg with Russian troops, while the mother stays behind in Mannheim with the two sons. Friends and relatives help the family and enable the two gifted children to attend the lyceum in the former Jesuit College in Square A 4.

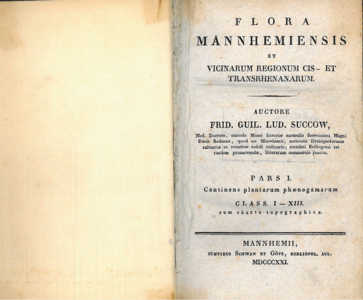

Together with his brother, Karl Friedrich enjoyed exploring the meadows and forests of Mannheim. He became interested in botany at an early age and, even as a schoolboy, helped Wilhelm Suckow, a naturalist and curator at the Friedrich Museum of Natural History, to research the "Flora Mannheimiensis". In the preface of the book, which was published in Latin in 1822, Suckow thanked Karl Friedrich for his great diligence in collecting the plants and skillfully describing where they were found.

In 1822, Karl Friedrich left the school with an excellent report. In it, he is certified that he "belonged to the first students in all branches of the institution through his capable and successful striving and has earned the respect of all his teachers through his good and modest behavior. A scholarship enables him to study theology at Heidelberg University.

After two years he breaks off his studies and travels to southern France and the Pyrenees on behalf of the "Württembergischer Reiseverein" to collect plants for herbaria. When he returned in the fall of 1825, he brought back more than 20,000 plants. He arranges and identifies them at the home of his uncle Franz Wilhelm Schimper, who lives in Offweiler, Alsace, and later at the home of his fatherly friend, the botanist and garden director Johann Michael Zeyher in his apartment near Schwetzingen Castle. Today, the district court is housed here.

At Zeyher's he met his foster daughter Sophie Wohlmann and became engaged to her. Although the engagement was broken off four years later, the two remained friends for the rest of their lives. In September 1826, Schimper also met the poet Johann Peter Hebel at Zeyher's just a few days before his death. Schimper was deeply impressed by Hebel and worshipped him from then on. Only a short time later, Schimper began to study medicine in Heidelberg. There he became friends with Alexander Braun and Louis Agassiz, whom he followed to Munich in 1828. In 1929 he was awarded a doctorate in philosophy "in absentia", i.e. without examination.

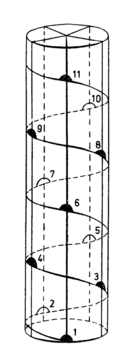

Much more important to him, however, was his botanical research, especially the study of the laws governing the leaf position of plants. Schimper illustrated the results of his research in a treatise published in 1829 in the Magazin für Pharmacie, using the example of the inconspicuous medicinal herb "comfrey," which he named "Symphytum zeyheri" after his paternal friend . The leaves of some plants are arranged at the same height on the stem, of others alternately. In some plants the leaves are arranged at the same height on the stem, in others alternately. If you think of a spiral line around the stem, the distances become measurable. When the spiral line, starting at the lowest leaf, has gone around the stem twice, one sees the 6th leaf again exactly above the starting leaf. With his "leaf position theory" Schimper proves that the arrangement of plant leaves follows geometric rules. He thus becomes the co-founder of modern botanical morphology, the study of the structure and form of organisms.

The "Description of "Symphytum Zeyheri" unfortunately remains Schimper's only scientific publication. In September 1834, Schimper lectured on the geometric design of plants at the naturalist conference in Stuttgart, but did not publish anything about it. Therefore, his friend Alexander Braun wrote a paper entitled "Dr. Karl Schimpers Vorträge über die Möglichkeit eines wissenschaftlichen Verständnisses der Blattstellung...." (Dr. Karl Schimper's lectures on the possibility of a scientific understanding of leaf position....), which appeared in the renowned journal "Flora" in 1835 and made Schimper's research known to the scientific community. Although Braun only wants to help him with this publication, Schimper is annoyed that the final version was not submitted to him.

Schimper later deals with many other botanical topics, such as the construction and branching of roots. He also discovers the ability of mosses to store water capillary and their resulting importance for the forest and the water balance of the landscape. Unfortunately, he cannot be persuaded to publish his findings as a scientific treatise, preferring instead to record his observations in numerous instructional poems, such as the "Mooslob".

What keeps us in the track? What saves us from the ice?

From thorny desertification? And country dust dragging?

What warms and brings the rain? What binds its blessings?

What saves and feeds rivers? What secures us pleasures?

The smallest and the great, The Gulf Stream and the mosses!

While botanists recognize the importance of Schimper's leaf position theory and appreciate it already during his lifetime, his achievements in the field of geology are recognized only long after his death.

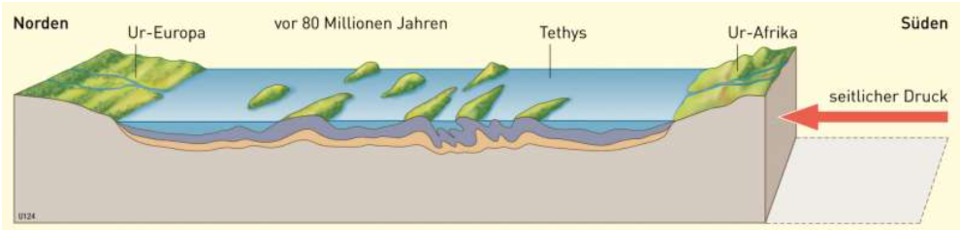

After receiving his doctorate, Schimper remained in Munich and turned primarily to geological topics. At that time, people had been trying for a long time to find out how huge boulders had arrived in areas from which they could not have come geologically. Many researchers explained this with volcanic activity, others thought that the boulders had been washed down by water floods after the uplift of the Alps.

In the winter semester 1834/35 Schimper gives a lecture on the geological history of plants and animals, and in the winter semester 1835/36 lectures follow on climate fluctuations, ice and warm periods. Schimper explains that warm and cold periods have been alternating for millions of years and concludes that the large erratic blocks in the foothills of the Alps were not transported to their present location by water, but by ice alone during the last "desolation period".

He travels to Switzerland in the summer of 1836, where he meets with glaciologists. In December of the same year, he visits his study friend Louis Agassiz in Neuchâtel, where he is engaged in studies of fossil fish and gives geological lectures.

During extended hikes, Schimper discovers the now famous Landeron glacial striae near Neuchâtel. These were formed when ice from huge glaciers began to slide and the rock carried along with it ground the bedrock smooth. This is an important indication of the once great extent of the glaciers and an unmistakable sign of a landscape shaped by glaciers.

Schimper wrote the ode "Ice Age", dated February 15, 1837 -his birthday- about this realization:

Ureis's Late Remnant, older than Alps are!

Ureis of that time, when the force of the frost

mountain-high buried even the south,

ebnen vehüllt so Gebirg' als Meere!

Schimper is unable to attend the annual meeting of the Swiss Society for the Entire Natural Sciences, which is held in Neuchâtel in July of the same year, and thus cannot report on his discovery. In the meantime, he was staying with his new bride Emmy Braun in Karlsruhe. Emmy is the sister of his friend Alexander Braun. Schimper became engaged to her two years after his separation from his first bride Sophie. Braun's second sister Cecilie is married to their mutual friend Agassiz.

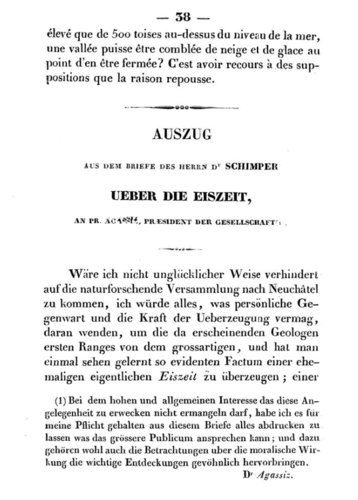

Guilelessly, Schimper leaves his detailed treatise "On the Ice Age" to his friend Agassiz, so that the latter will publish it at the meeting. Agassiz, recognizing the importance of the fundamental theory, recites Schimper's report and is soon hailed as the founder of the ice age theory, which he gladly accepts.

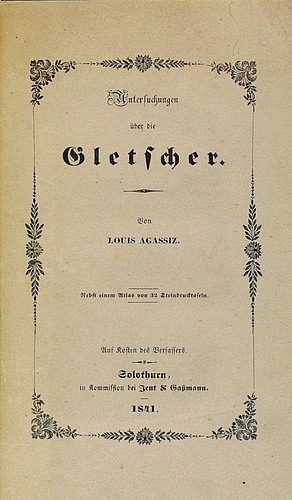

Schimper reacts irritably and full of anger, which increases the tension between him and Agassiz all the more. When Agassiz published his book "Untersuchungen über die Gletscher" (Investigations on the Glaciers) in 1841 after his own glacier research, he did not mention Schimper with a single word. Even with enlightening messages, Schimper is not able to assert his priority claims against the urbane and successful Agassiz. In his ode "Gebirgsbildung" Schimper complains about the lack of recognition and the betrayal of his friend, whom he compares to a thieving magpie:

The Galilean torture perpetrated on the singer of the ice age,

Or with thieving sense him, deep flattening, stole from,

While Agassiz chatter of a thieving magpie the crowd

Honest and stupid and dumb or applauding marvels.

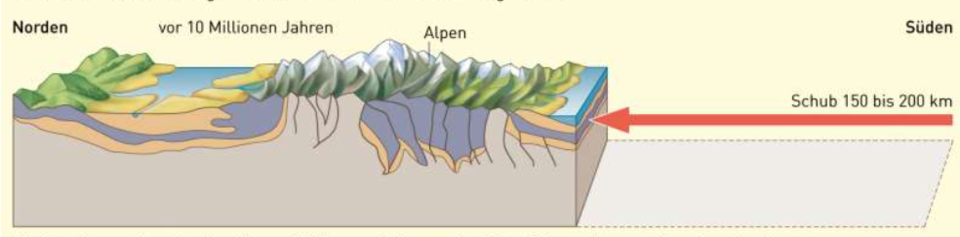

Fortunately, Schimper soon finds a new task that fills him. Crown Prince Maximilian of Bavaria commissions him in the spring of 1840 with the geological exploration of the Bavarian Alps and the Rhine Palatinate. Schimper spends more than 6 months in the mountains collecting rock samples. During his investigations, with his own unbiased observation, he comes to the fundamental conclusion that the Alps were unfolded by a horizontal pressure and not, as was believed at the time, by a vertical pressure acting from below.

In his report to the natural scientists' assembly meeting in Erlangen at the end of 1840, which he wrote down on a box of specimens, the pugnacious Schimper sharply contradicted the prevailing theory of mountain building. He writes: "In the face of the Alps, it is an incomprehensible ridiculousness to want to deny the mechanical character of the uplifts, passages and supports." He states that all the conditions he has seen in the Swiss and Bavarian Alps, as well as in the Jura, prove "that the uplift of both convex and stratified masses has arisen as a result of that horizontal pressure which a heavy earth's crust had to give itself when the earth's core on which it rests became smaller," that is, that a horizontal pressure upset the shrinking earth into folds.

Leopold von Buch, study friend of Alexander von Humboldt and prominent representative of the prevailing opinion, does not miss the opportunity to read Schimpers letter to the assembly of natural scientists himself and to tear the explanations apart. It will take another thirty-five years until Schimper's thesis of the fold mountains will be accepted. However, the recognition is given to the Austrian geologist Eduard Suess when he takes up Schimpers findings in his work "The Origin of the Alps" without mentioning him by name.

Despite the scathing criticism, Schimper continued his geological investigations in the Rhine Palatinate with great zeal, but did not deliver any more reports. This leads to a dispute with Crown Prince Maximilian, father of the later Bavarian King Ludwig II. Schimper falls out with the Crown Prince, who then stops paying him a salary. This also put an end to Schimper's hopes for a position in Munich and a further career.

After he was denied recognition for his scientific achievements and a professorship at a university, which Schimper had hoped for so much, and after he was unable to support a family with a permanent position despite the urging of his bride, Emmy broke off the engagement after eight years. This hits Schimper so hard that his friendship with Alexander Braun now breaks completely.

Devastated, embittered and completely penniless, Schimper returned to his native Mannheim at the end of 1842 and struggled to make ends meet as a private scholar giving lessons. However, this did not prevent him from continuing his research and also from studying river currents and the laws governing the arrangement of river debris. In 1843, he summarized his diverse natural history observations on the prehistoric climate, such as vegetation and the eyes of animals, which indicate sunshine, dry cracks, which prove drought, wave furrows, which are witnesses of the wind that had dug them into the rock long ago, and foliage embedded in Tertiary strata, which indicates seasons, in a small paper entitled "On the Weather Phases of the Prehistoric World". This makes him the founder of paleoclimatology, a branch of geology that studies the various climatic conditions in the course of the Earth's history and uses them to draw conclusions about future climate.

His financial worries, which accompanied him throughout his life, were alleviated in 1845 by a small pension granted by Grand Duke Leopold of Baden . In 1849, he leaves Mannheim, which is agitated by the Baden Revolution (our panel Wege zur Demokratie (Paths to Democracy) tells about these events), and moves to Schwetzingen, where he continues his research tirelessly without employment, lonely and in modest circumstances in a garret of the "Pfälzer Hof". He still gives occasional lectures and writes "missives" and letters. But he still cannot bring himself to write down and publish his important research results systematically and coherently instead of on flyleaves or book covers. He prefers to strive ceaselessly for new things and to devote himself to his research. He finds fulfillment in this as well as in writing instructive poems full of wit and also irony. His didactic poems have survived in two volumes of poetry.

Since there are no scientific publications by him, the ingenious natural scientist falls into oblivion. Thus it happens that his lectures on mosses are attributed as a matter of course to his Strasbourg cousin Wilhelm Philipp Schimper, known as "Moosschimper", even if the latter is not even present at the meeting, which offends Karl Friedrich and strains his relationship with his cousin.

Grand Duke Friedrich von Baden, the son of Grand Duke Leopold, not only increases Schimper's pension, but also provides him with a small apartment in Schwetzingen Palace. And Schimper also meets his first bride Sophie again, who moves to Schwetzingen in 1863. She now takes care of him and also nurses him when, in June 1867, he is attacked in the evening on his way to see her and is so badly injured that he can hardly move. In addition, he was increasingly tormented by dropsy. After months of illness, the brilliant naturalist dies on December 21, 1867, and is buried near the graves of Hebel and Zeyher in Schwetzingen.

"Schimper is both a researcher and a thinker, equally gifted at imagining possibilities and studying reality." With these words Melchior Meyr remembers the deceased friend from Munich days (Flora from 11.02.1868).

But most aptly Schimper describes his life itself in the poem:

On the day Galilei came,

I came late enough;

Sure that his liberated spirit

With patience looked upon me

Independently quiet on every track

As a child I already follow nature

The Alps I've scouted

For the splendor of their flora,

And explored them again

For strata and shafts;

I have also shown you the ice age

And other things of which you are silent.

And also experienced how a heart

Rejoices and endures bitter pain!