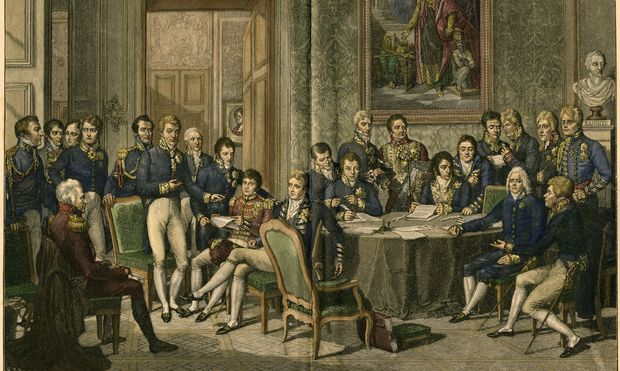

The wars of liberation end Napoleon's rule. The Congress of Vienna of 1814/15 restores absolutism and reorganizes the German states. The Rhine Palatinate falls to the Kingdom of Bavaria, which severely restricts the civil rights granted by the Code civil and imposes high customs duties and taxes. In contrast, the Grand Duke of Baden, Charles, married to Napoleon's stepdaughter Stephanie de Beauharnais, gives his people a constitution granting civil rights on August 29, 1818.

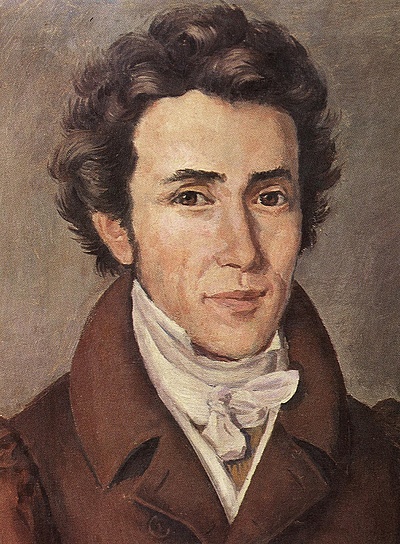

Philipp Siebenpfeiffer, Johann Georg Wirth, Friedrich Hecker, Gustav Struve

Under Napoleon Bonaparte, France conquers large parts of Europe. After the Peace of Lunéville in February 1801, the Palatinate also belongs to the French Republic. The ideals of liberty, equality, fraternity take hold, and the Code civil guarantees the Palatines personal freedom, private property, equality before the law, civil marriage and also divorce. Court proceedings are now public, judges are independent, and juries judge criminal cases.

The wars of liberation against Napoleon gave rise to a national consciousness in Germany. In 1815, not only was the "German Confederation," a loose association of 39 princes, founded, but also the "German Fraternity" in Jena. At the Wartburg Festival in 1817, it called for a German nation-state and the abolition of absolutism. When the fraternity member Karl Ludwig Sand murders the poet August von Kotzebue in his apartment in Mannheim on March 23, 1819, the Karlsbad resolutions ban the fraternities, monitor the press and universities, and punish free-market activities.

With the July Revolution of 1830, the French force their king to abdicate and enthrone Louis Philippe as citizen-king. This spurs the freedom movement throughout Europe, to which the Bavarian King Ludwig I responds by restricting freedom of the press and assembly.

The lawyers and journalists Dr. Philipp Jakob Siebenpfeiffer (1789 - 1845) and Johann Georg Wirth (1898-1848) protested against this and founded the "Deutscher Preß- und Vaterlandsverein" in early 1832.

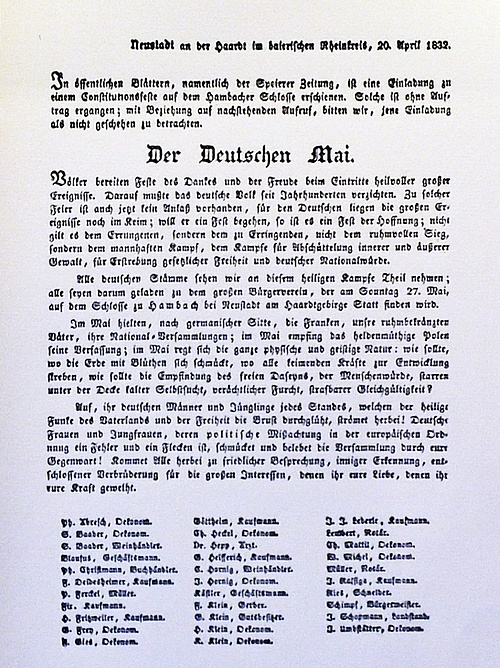

Within a very short time, it has 5,000 members throughout Germany. When the "Neue Speyerer Zeitung" in April 1832 invites to the Bavarian Constitution Day on May 26 at Hambach Castle, Siebenpfeiffer and Wirth use the opportunity and rework the invitation to a national festival on May 27, which is supposed to set a sign for national unity and civil freedom.

The invitation was accepted by some 30,000 men and women from various walks of life, mainly from the Palatinate and other German countries. But delegations from Poland, France and England are also there, as is a large delegation of fraternity members from Heidelberg. In the early morning of May 27th 1832, the procession with black-red-gold flags marches up from Neustadt's market square to Hambach Castle, accompanied by the ringing of bells. During the procession, the song "Hinauf Patrioten zum Schloß, zum Schloß" ("Up patriots to the castle, to the castle"), written by Siebenpfeiffer, is sung.

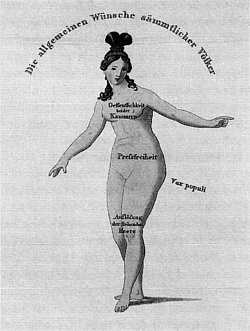

In fervent speeches, Dr. Philipp Siebenpfeiffer, Johann Wirth and other speakers invoke national unity, political sovereignty of the people and civil liberty, especially freedom of opinion and speech, freedom of the press and assembly, and equal rights for all citizens, including women. Siebenpfeiffer calls for people to no longer bow under the yoke of princes, but to fight for freedom. He ends his speech with the words "cheers to every nation that breaks its chains and swears with us the covenant of freedom." There are also calls for a constitutional monarchy. Wirth even calls for a federal republic in a confederated Europe.

In the face of such provocative demands, the German Confederation reacts with intensified repression. To prevent a revolution, Bavarian troops enter the Palatinate. Political associations and meetings are banned, as is the wearing of black-red-gold insignia. Only a few participants in the Hambach Festival are able to flee into exile. Siebenpfeiffer, Wirth and other speakers are arrested for "attempted incitement to overthrow the state government" and put on trial in Landau. Although Siebenpfeiffer and Wirth were acquitted at the trial, they were later sentenced to imprisonment by the "breeding police court" for insulting public officials.

Friends enable Siebenpfeiffer to escape from prison in November 1833. He flees to Switzerland, where he becomes a professor of criminal and constitutional law in Bern. Wirth emigrates first to France in 1836 and then to Kreuzlingen in Switzerland in 1839. In 1847 he moves to Karlsruhe and is elected to the German National Assembly. A short time later he dies in Frankfurt.

The Hambach Festival remains one of the most significant events in the history of German democracy, making Hambach Castle the cradle of German democracy and European unification. The desire for freedom and unity remains and later prepares the ground for the Baden Revolution of 1848.

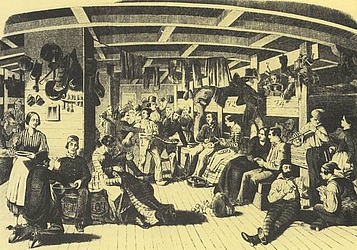

The industrial revolution that began at the beginning of the 19th century led to the decline of manufactories that had become unprofitable and plunged many craftsmen and workers into unemployment and poverty. The bad harvests of the years 1845 - 1847 trigger famines. Many Palatines emigrate to America to escape hunger and poverty. Discontent grows. There are riots. The workers demand social justice, the peasants liberation from oppressive tax burdens and the liberal middle classes finally the foundation of a German nation state, from which they expect economic advantages. Already in the Vormärz, the first different concepts of moderate liberals and radical republicans become apparent, which will later lead to a split in the revolution.

Friedrich Hecker and Gustav Struve became the leaders of the Baden Revolution. Both were among the radical democratic republicans.

Born in Eichtersheim on September 28, 1811, Hecker grew up in a middle-class liberal home. He attended the Grand Ducal Lyceum in Mannheim from 1820 to 1830 and studied law in Heidelberg. In 1834, he graduated summa cum laude as a doctor of law. After completing his legal clerkship in Karlsruhe, he left the civil service. But it was not until 1838 that he was able to take up a position as an advocate at the Grand Ducal High Court. There he met his colleague Gustav von Stuve.

Gustav von Struve, born in Munich on October 11, 1805, first attended the Lyceum in Stuttgart and from 1817 to 1822 in Karlsruhe and then studied law in Göttingen and Heidelberg, where he joined the Old Heidelberg Fraternity. In 1827 he became an attaché in the state service of Oldenburg, but his views soon caused offence. After brief stints in Göttingen and Jena, he settled in Mannheim as a lawyer in 1833 and became a senior court advocate in 1836. When he married Amalie, the adopted daughter of a Mannheim language teacher, in 1845, this marriage, which was not in keeping with his status, led to a break with his family and he gave up his title of nobility. The self-confident Amalie Struve supported her husband in his political activities and was active in the women's movement.

At first, the two men had little contact with each other. Hecker, a friend of Adam von Itzstein, is elected to the Mannheim municipal council in 1842, admitted to the "Räuberhöhle" gentlemen's society that still exists today, and also becomes a deputy in the second Baden chamber in Karlsruhe. He is an excellent speaker and quickly becomes known as a spokesman for the liberal-democratic opposition.

When the unrest in France in 1848 leads to revolution, the Bourgeois King Louis Philippe I is forced to abdicate and on February 24 the Republic is proclaimed. The news quickly reached Baden and the Palatinate and acted as a beacon.

On the evening of February 27, 1848, Hecker and Struve convene a citizens' assembly in the auditorium of the Grand Ducal Lyceum in Mannheim, A 4, 4, which becomes the first rally of the revolution in Germany. In a petition addressed to the Baden government, they demand "prosperity, education and freedom for all classes of society, without distinction of birth or class," a constitutional constitution and an all-German parliament, freedom of the press, jury courts, people's armament, the right of assembly and association, and an amnesty for political offenses.

These so-called March demands become the basic program of the 1848 Revolution and quickly spread throughout all German states. Under the impact of the events, one of the first liberal March Ministries is appointed in Baden as early as March 9.

When the "pre-parliament" met in Frankfurt on March 30, 1848, Hecker and Struve were also present. However, their call for a republican Germany was not accepted by the supporters of a constitutional monarchy. Disappointed, they left the meeting and proclaimed a republic in Constance on April 12. Under Hecker's leadership, a group of armed freedmen set out on the morning of April 13 in the direction of Karlsruhe to capture the residence and depose the grand duke.

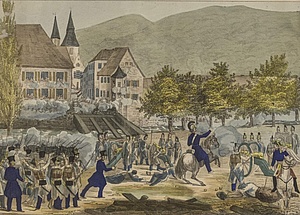

But only about 800 participants join the Hecker march on the way. The hoped-for broad support for the popular uprising failed to materialize. On April 20, the revolutionaries were crushed by troops of the German Confederation near Kandern. Hecker and Struve are able to flee to Switzerland. Their names are removed from the list of lawyers.

In Mannheim, where the vigilantes set up barricades near the Rhine bridge, there was a brief skirmish on April 26, 48, but the military superiority of the Bavarian and Hessian troops stifled further rebellion.

Hecker emigrates to America, buys a farm in Illinois and grows wine. He supports Lincoln's election as president, campaigns for the abolition of slavery and takes part in the wars of secession on the side of the Union. He dies on his farm at the age of 69.

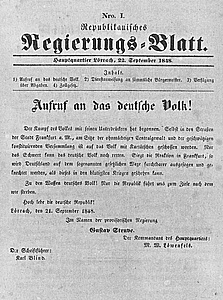

Struve, on the other hand, does not give up, but undertakes another uprising. On September 21, 1848, he arrived in Lörrach from Basel with 50 men. There he raises the red flag and proclaims the German republic from the balcony of the town hall. The irregulars set off for Karlsruhe.

But already near Staufen, the grand ducal soldiers put down the Struve putsch and take Struve and his wife Amalie prisoner. Both are convicted of attempted high treason. Amalie is imprisoned in Freiburg until April 1849, Gustav Struve is taken to the Raststatt fortress.

On March 27, the National Assembly in St. Paul's Church adopts the constitution of the German Empire and elects Frederick William IV emperor. But Austria and the German states do not recognize the constitution, and the Prussian king rejects an imperial dignity based on a constitutional monarchy. As a result, uprisings flare up again in May. When the soldiers of the Rastatt fortress mutinied, to which Amalie contributed with her agitation, her husband was transferred to the Bruchsal penitentiary on May 12, but was freed by revolutionaries the following night. Grand Duke Leopold flees to Alsace and the liberal lawyer Lorenz Brentano forms a provisional republican government.

However, when Prussian troops enter Mannheim on June 22 and force the surrender of the Baden revolutionaries in the Raststatt fortress on July 23, the revolution has finally failed.

Struve and his wife Amalie go to Switzerland, where they are soon expelled for agitation. They emigrate to the USA via France and England in 1851. Like Hecker, Struve supported Abraham Lincoln and took part in the Civil War against the Southern states. When the Grand Duchy of Baden grants impunity to those involved in the revolution in 1862, Struve returns. Amalie had died shortly before during the birth of their daughter. Gustav Struve dies on August 21, 1870.

Although the Baden Revolution was crushed, the desire for freedom and civil rights remained. The Hambach Festival and the Baden Revolution were paths to our democracy today, in which the demands of the Hambach Festival and the Baden Revolution have all been fulfilled. However, democracy must not be taken for granted. We must not forget that it was fought for.